|

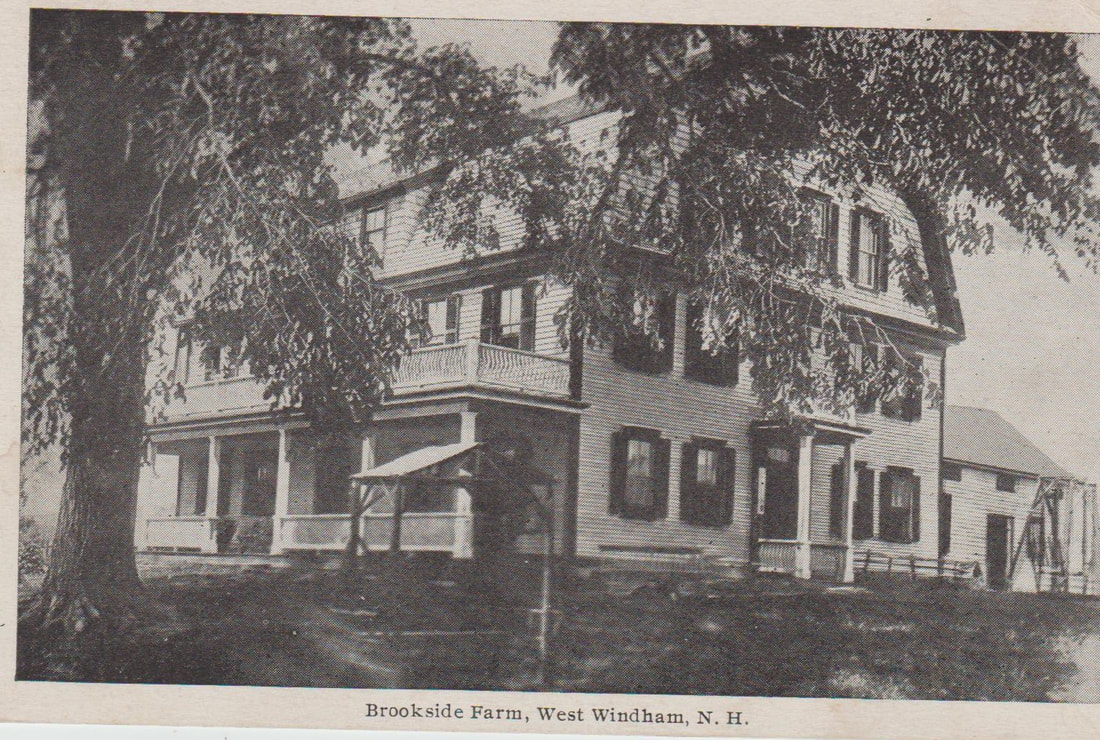

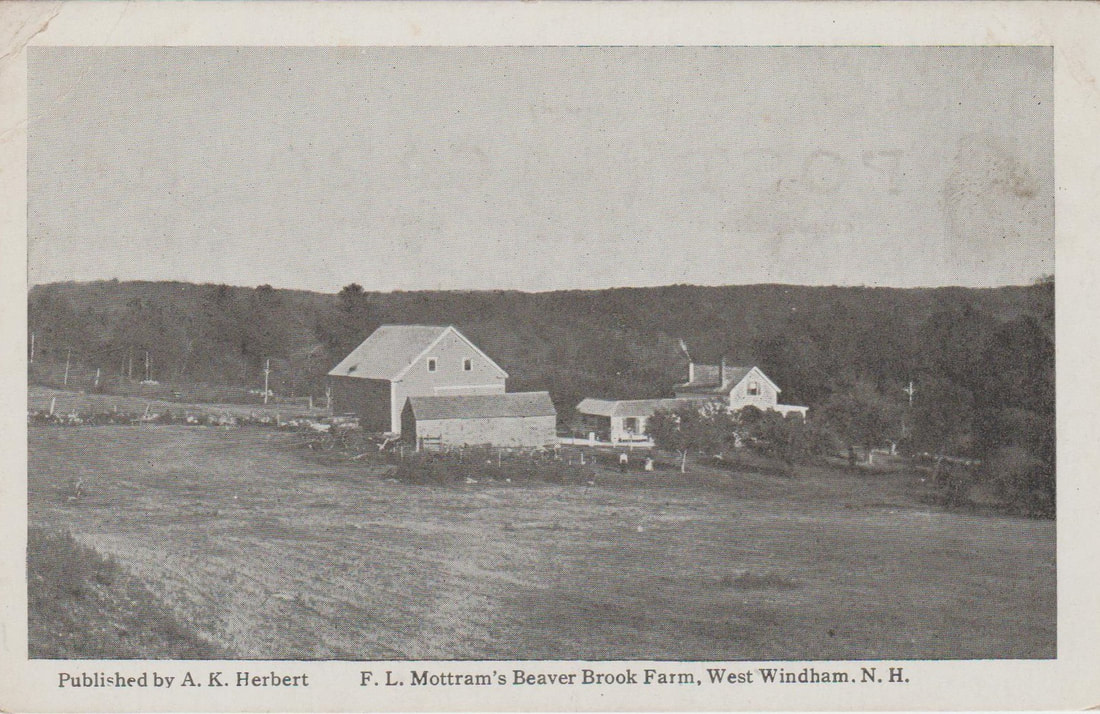

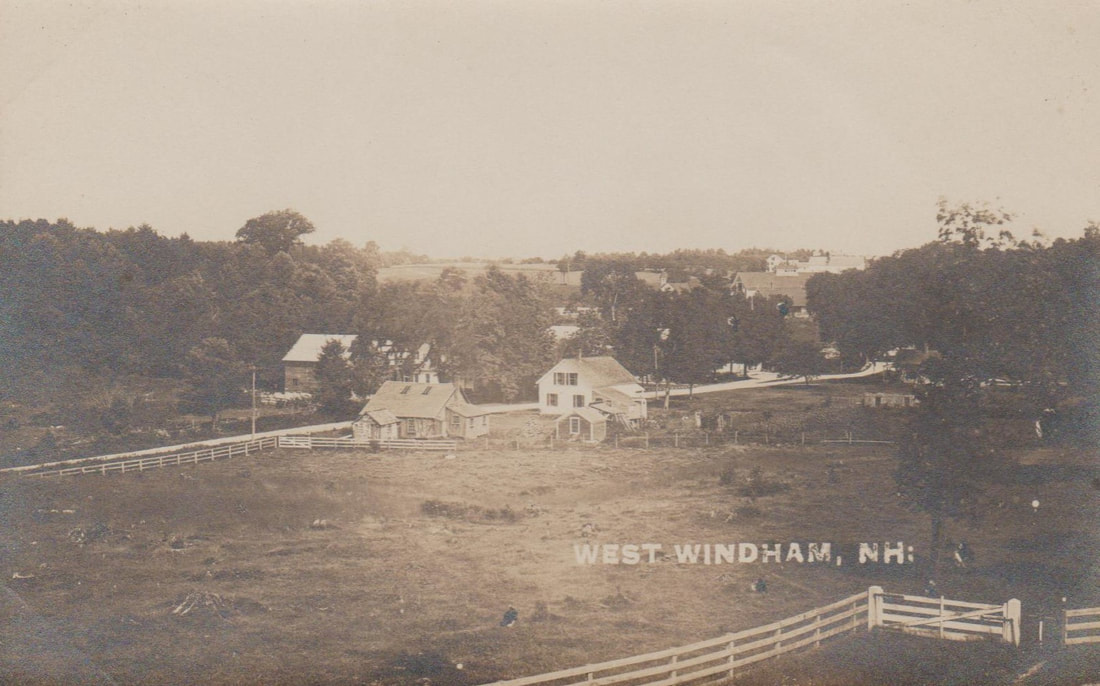

In the summer of 1904, readers of the classified ads in The Boston Globe would inevitably come across numerous ads for summer boarding houses located in the more rural areas outside of Boston. Promising an escape from the crowded, hot city, operators of boarding houses were able to generate additional income, and possibly even exchange room and board for some chores on the farm. An unidentified "private family" in Windham ran the simplest of ads, promising just a "quiet place, plenty of milk". While we'll likely never know how successful this one line ad was, it's basic amenities would certainly have appealed to some. Many of those running boarding houses in Windham were a bit more verbose and complete with their advertisements. At Beaver Brook Farm, F. L. Mottram rented a "limited" number of rooms at the bargain rate of $7 per week. For $7 a vacationer from the city could enjoy "attractive surroundings, abundant shade", conveniently located near a train station in West Windham. $7 seems to have been the going rate at that time, as other boarding houses in town rented rooms at that low price. What bought pleasant surroundings and shade at Beaver Brook Farm would have also paid for a week's stay at Brookside Farm in West Windham. Brookside offered not only a "pleasant location", but amenities including a "good table", a piano, "large airy rooms", nearby fishing and boating, as well as "church accommodations." Moving across town, $7 also paid for a week at Elm Farm. For just $1 per day, boarders at Mrs. Kane's Elm Farm were treated to "good milk, eggs, cream, berries" as well as a piano and "free" church accommodations, and even a telephone connection! The lure of a few days in the country at a farmhouse endured for decades, as although the ads mentioned above date from the first quarter of the twentieth century, newspaper ads seeking summer boarders appeared in newspapers as far back as the 1880s. In that decade an unidentified Windham resident, with post office box #75, advertised "fun and comfort" and asked that interested parties inquired for more information.

0 Comments

The late 19th century is notable for a rise in medical quackery. Before increased regulations by the FDA in the first quarter of the 20th century, entrepreneurs throughout the nation capitalized on a trend towards the use of patent medicines to cure all illnesses from cancer to the common cold; whatever you had you could be fairly certain there was a bottle of something to cure it! Many of these "medicines" were combinations of herbs, alcohol, and often useless ingredients. While many of those peddling patent medicines never found great success, there are a few who built large brands and great wealth. One such operator was C. I. Hood of Lowell, MA. What started with a single medicine expanded into a line of liquids and pills, sold as being effective remedies for purifying the blood and curing any ailment you might have. Hood's Sarsaparilla was one of the company's best selling products, and its sales were supported by a significant advertising budget. Hood used a variety of advertising premiums, such as trade cards and souvenir photographs of the world, to market his most popular medicine. Included in the advertising strategy were newspaper ads which would have appeared in newspapers throughout New England. Many ads featured testimonials from those who saw their health improve after taking the famous sarsaparilla. Undoubtedly folks in Windham gave the miracle liquid a try, and according to an 1882 newspaper ad, a Mrs. Cole of Windham had great success with the concoction. According to the ad she was covered in 37 "terrible sores" and her life was saved after taking Hood's Sarsaparilla. Whether Hood's medicine was responsible for her recovery is unknown, but one can be fairly certain there was a bottle or two of Hood's Sarsaparilla in the homes of Cole's friends and neighbors once they witnessed her improvement.

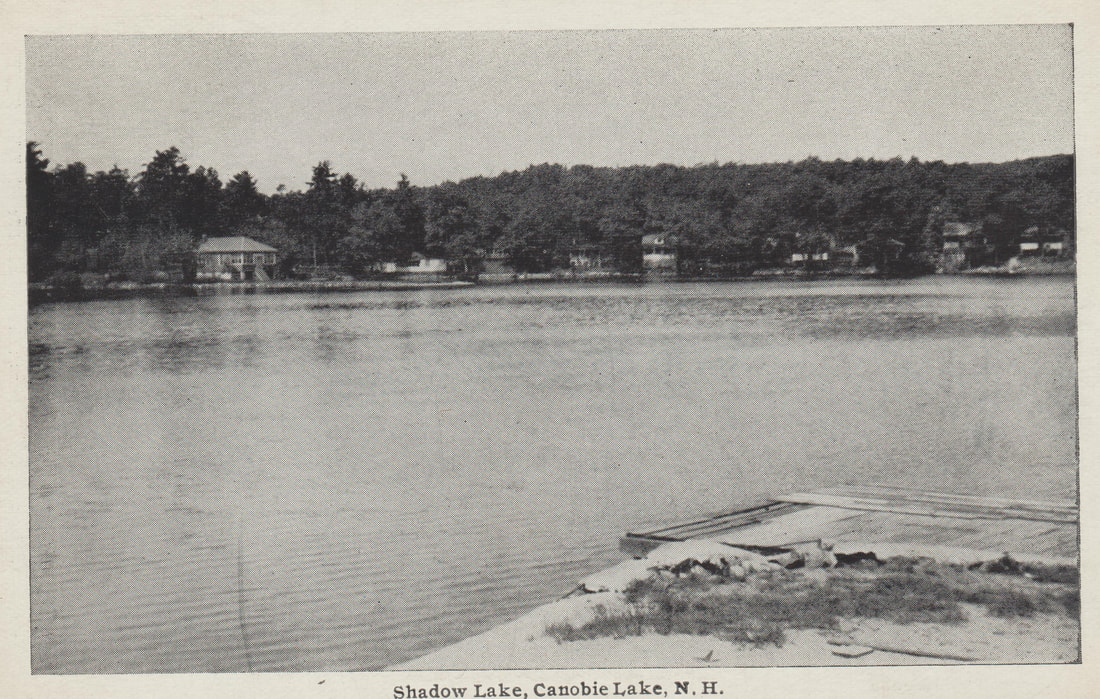

While the shores and waters of Shadow Lake lie partially in Windham and Salem, the local prominence of Cobbett's Pond, the Windham shore of Canobie Lake, and the several other ponds in Windham, often shadow over that of Shadow Lake. However, on a summer day in 1953, Shadow Lake was given national attention likely never seen by another Windham pond or lake. On Monday, July 20, 1953, Lawrence W. Allen was sitting on a raft at Shadow Lake when a friend sharing the dock with him hit him on the back. The force of the friendly blow knocked Allen into the water, and when he returned to the surface he quickly realized he had lost his upper set of dentures. Not an experienced diver, Allen hired the services of a diver to attempt to recover his $150 set of false teeth. Sensing public interest in the mishap of Allen, the Associated Press picked up the story and, within just one day, readers across the nation were able to open their local paper and read about the search for false teeth at the bottom of a lake they had likely never heard of in the small town of Windham, New Hampshire.

There are several towns by the name of "Windham" located throughout the nation, located in Maine, Pennsylvania, New York, and other states. While these towns share a common name, the story behind the name varies from town to town. For example, Windham, Maine was named for the town of Wymondham in Norfolk, England. Windham, New Hampshire is generally accepted to be the namesake of Sir Charles Wyndham, 2nd Earl of Egremont.

Born in 1710, Sir Charles Wyndham was born into a politically powerful English family; his father, Sir William Wyndham served as Secretary of War and the leader of the House of Commons. According to Max Egremont, a descendant of Sir Charles Wyndham, and the current 2nd Baron Egremont, Sir Charles Wyndham was "the heir to a huge fortune, ... one of the richest peers in the kingdom." Charles Wyndham was educated at the Westminster School in London, as well as the historic Christ Church in Oxford. After completing his formal education, Wyndham "went on a Grand Tour of Europe, visiting Germany, France and Italy. While traveling through Europe, Wyndham developed an appreciation for art and collected paintings and sculpture, which were brought back to his family estate, the Petworth House; some of the art he collected still remains in the Petworth House, which is partially occupied by his descendants. After returning from his jaunt through Europe, Wyndham became involved in politics, and served as a Member of Parliament from 1734 to 1750. During his tenure as a Member of Parliament, he became a close friend of Benning Wentworth, the colonial governor of New Hampshire from 1741 to 1766. When the residents of the portion of Londonderry that would become Windham petitioned for incorporation in 1741, they did so knowing approval from Governor Wentworth was required for their effort to succeed. Although, the identity of the person, or persons, who chose the name "Windham" are likely lost to history, it can be surmised the name was chosen to please Governor Wentworth; naming the town after a close friend of the Governor would certainly give the petitioners a leg up in the petition's approval process. When Windham became a town on February 12, 1742, Charles Wyndham was just at the beginning of what would become a successful career, not only as a politician, but as a family man. In 1751 he married Alicia Maria Carpenter, the daughter of an Irish peer, and the couple raised four sons and three daughters together. Just a year after the birth of his last son, Wyndham was appointed secretary of state for the southern department, the most prominent position of his career. Wyndham's tenure as secretary of state is best summarized by Max Egremeont: "He was competent rather than exciting, trying (and generally succeeding) to make peace with France on terms that were favourable to the British. In 1763, he was involved in the prosecution of the journalist and politician John Wilkes who had published supposedly libellous comments on King George 111 in his paper The North Briton." Unfortunately, Wyndham would not hold his post for long. In 1763 he suffered and apoplectic stroke and died. Wyndham family legend holds that his death may have been caused by overeating, and that a few days prior to his death, Wyndham had remarked "but three turtle dinners to come, and if I survive them I shall be immortal." Alas, he evidently did not achieve immortality. However, his name has proved to be immortal, with North Egremont and South Egremont, Massachusetts bearing his name, and our town of Windham serving as a permanent legacy of Sir Charles Wyndham, 2nd Earl of Egremont. While the annual boat parade on Cobbett's Pond has survived changing times over the past several decades, one related tradition has not. The inaugural Cobbett's Pond beauty contest was held in 1958, and quickly became a popular event in the community. Miss Cobbett's Pond was chosen by a panel of judges at a dinner and beauty contest held at Town Hall. Prior to the dinner, all of the contestants participated in a parade where their family, friends, and fellow Cobbett's Pond residents had their first chance to catch a glimpse of all the candidates before the title of Miss Cobbett's Pond was bestowed upon a single young woman a few days later. While the contest was only open to residents and campers of Cobbett's Pond, the committee included residents from surrounding towns; during the 1960 contest the head of the committee in charge of soliciting entries was a resident of Nashua. A committee comprised of local teenagers was tasked with canvassing the cottages and homes along Cobbett's Pond and registering girls between the ages of 12 and 18 as candidates in the annual contest. One lucky entrant, after being crowned Miss Cobbett's Pond, had the honor of being escorted around the pond during the annual boat parade, usually held a couple weeks later. Wearing a crown and riding on a small, decorated motorboat, the first Miss Cobbett's Pond, Marie Chadwick, is shown in the photograph above, taken during the 1958 boat parade.

The long history of Cobbett's Pond is filled with many happy memories made by residents and vacationers alike. However, the pond's history is not without its darker moments; there have been accidents and drownings throughout its history. While these incidents have, fortunately, been scarce, they are nonetheless a significant part of the pond's story. Not all of these stories of misfortune and accidents have ended in tragedy though. On Tuesday, September 1, 1953, Carl Church Jr, a swim instructor at Nashua's public pool, was enjoying his day off at a beach on Cobbett's Pond. Church, a strong swimmer, had ventured out to raft where he had been sitting when he heard a cry for help. A young girl who had just recently learned to swim had been attempting to make her way to the raft when she became tired. Not being able to complete her trip to the raft or make her way back to the beach, her father swam to her, but was pushed under by his daughter's panic. Church moved quickly, separated the pair, and helped the girl to the raft. After resting for a bit, Church helped the young girl back to the beach; her father had been able to save himself once Church separated him from his daughter. In the following decades safety requirements became more stringent, requiring life guards and other precautions for the public beaches still remaining on the shores of Cobbett's Pond.

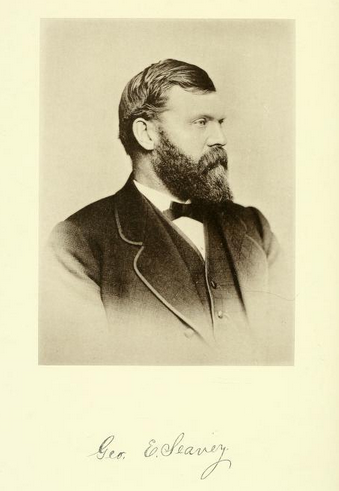

George Seavey could be called the lumber baron of Windham. With mill operations and lumber interests in town, he dominated the lumber industry in town at the turn of the twentieth century. As a successful businessman, his name is not scarce in the index of the county register of deeds during late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. Many of the deeds are commonplace land transactions, but in 1902 one particular deed attracted the interest of area newspapers. On November 14, 1902, George Seavey traded 20,000 feet of "white pine planks loaded on a car at Windham Junction" for a 68 acre plot of land in town. In receipt of the 20,000 feet of wood planks were Jacob Cook of Minneapolis, and numerous heirs of William H. Lunt, of Windham, who were spread out throughout the country. With over three dozen individuals involved, what would otherwise have been a short deed, spans three pages; nearly one page is filled with the signatures of Lunt's heirs. The land was located in the vicinity of the Junction, where Seavey operated his business, and was bounded by the Manchester & Lawrence Railroad.

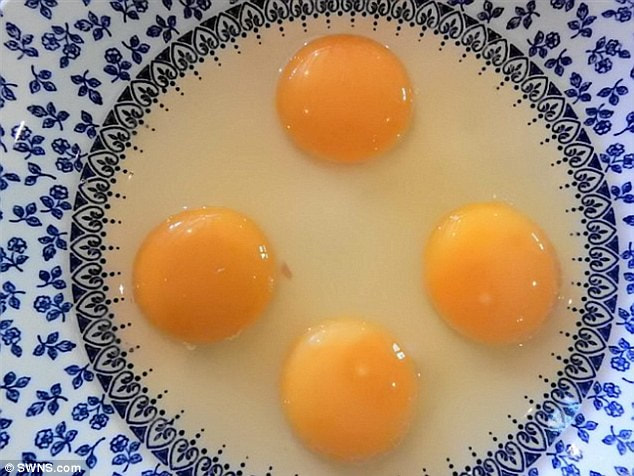

Learn more about George Seavey Paul Ray Myers was hardly the only farmer in Windham raising chickens in 1939. Myers was in the egg business and he primarily sold his product through the New Hampshire Egg Auction in Derry. According to "Images of America: Derry," the auction company processed millions of eggs a year during its 11 year history, having operated from 1930 to 1941. One of their egg candlers, Roger Beliveau, sorted an almost unbelievable 90 million eggs between 1930 and 1934. It was not until after he had candled the 90 million eggs that Beliveau discovered his first, and the company's first, four-yoke egg in 1934. While the odds of finding one of these eggs has been estimated at 1:11-billion, this four-yolk egg would not be the only one of his career. Just five years after his first discovery, he made another in June of 1939. After candling a three-ounce egg and noting an appearance of four yolks, Beliveau carefully broke open the egg and discovered it contained four yolks, but an average amount of egg white. The hen that laid the egg was one of Paul Myers' brood and had been hatched in New Hampshire several months earlier on January 10. According to a period article by The Portsmouth Herald, two-yoke and three-yoke eggs were not uncommon in the state during the summer months, but the discovery of a four-yoke egg was almost unheard of. A census of agriculture statistics in New Hampshire reported over 175 million eggs being produced in New Hampshire in 1939, meaning a single four-yoke egg would be expected to be found in 63 times that production level, and certainly would not have been anticipated in a batch of just 175 million eggs, especially when one had been found just five years prior. When considering the just under nine million eggs produced in Rockingham county that year, and the even fewer eggs produced in Windham, the odds stack up even greater against a four-yoke egg being not only discovered, but originating from Windham

With nearly three hundred years of history, odds have it that Windham has been home to its share of less-than-exemplary citizens. One such citizen was Eben Woodbury. Not much is recorded about Woodbury or when he first turned to a life of crime. If any of his neighbors in Windham were not aware of his criminal past, they may have been alerted to his activities when his exploits earned him a brief mention in The Portsmouth Herald. On April 28, 1899, Woodbury was arrested at his farm in Windham on robbery charges. Accused of multiple house robberies in Nashua, he was brought to the city after his arrest to stand trial. A reporter for The Portsmouth Herald uncovered Woodbury's "reputation for being a sneak thief" who had previously spent six years in prison; a four-year stretch at the Massachusetts state prison and a short two years at the New Hampshire state prison. At the time of his arrest in Windham it was alleged Woodbury may have been responsible for a string of robberies in Manchester, Lawrence, Haverhill, and Lowell. If the allegations are any indication of the time he dedicated to his sideline, Woodbury may have spent just as much time travelling between states to burglarize homes as he did farming.

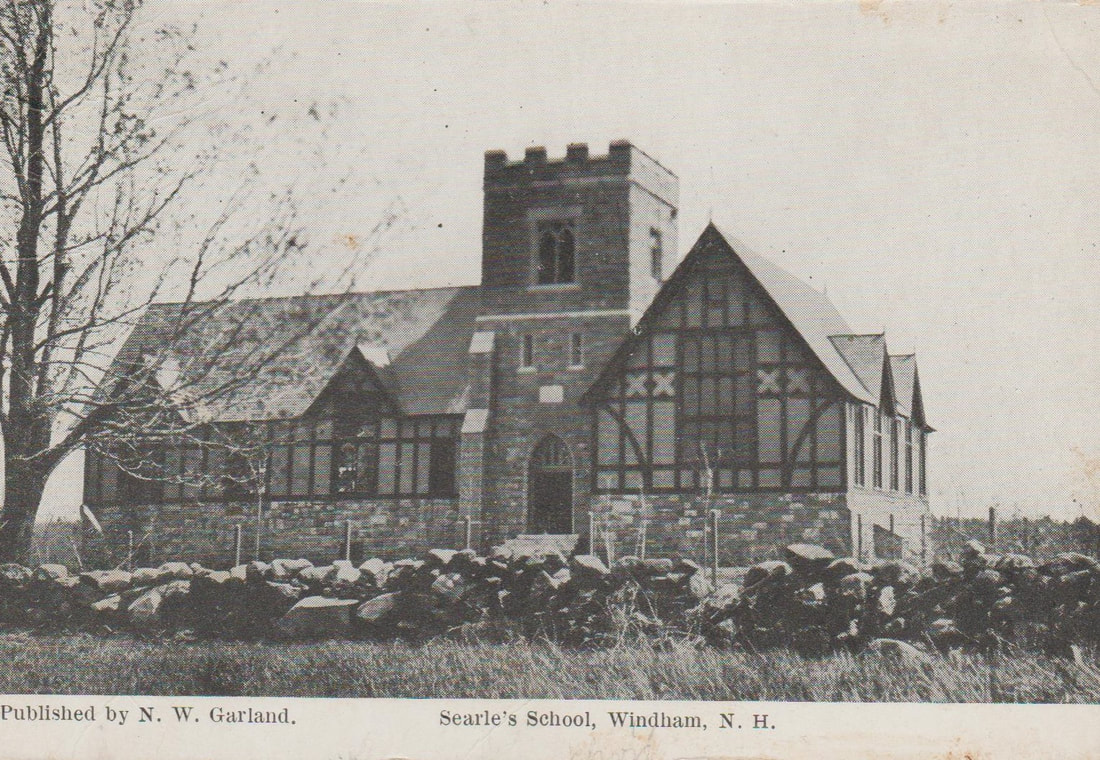

When one thinks of the community of Windham in the 1930s, they are likely picturing idyllic country scenes, summers at Cobbett's Pond, and a simpler way of life. There is probably not even a remote possibility one would picture the less-than-pleasant events of Depression era Windham, such as accidents on Cobbett's Pond, or even a kidnapping at Searles School. According to The Portsmouth Herald, on October 24, 1932 a Mrs. Josephine Stutz of Boston appeared before a police court in Portsmouth having been charged with kidnapping her niece from Searles School in Windham. Just two weeks earlier Mrs. Stutz, who also went by Mrs. Jarrow, had gone to Searles School and took her 15-year-old niece, Sophie Jaroskepski from her class. Jaroskepski, who lived in the Canobie Lake district, had previously written her aunt to express her desire to live with her aunt in Boston. Despite having been told by the Rockingham County Solicitor that she could not take her teenage niece out of New Hampshire without the consent of the girl's mother, Mrs. Stutz ignored the warning and brought Sophie back to Boston with her. When the pair arrived at the aunt's home on Commonwealth Avenue Mrs. Stutz informed her niece that she must abandon her surname and instead go by the name Sophie Jarrow. Likely alerted by Sophie's mother, the Boston police began searching for Mrs. Stutz and Sophie. About a day after the kidnapping Mrs. Stutz learned that the police were looking for her and turned herself in at a Boston police station and informed the officers she would return the girl to her New Hampshire home, which she promptly did. When Mrs. Stutz was eventually brought before the police court she was ordered to be held on $200 bail to later appear before a grand jury. Unfortunately it seems the conclusion of the case did not garner the same publicity as the kidnapping, as the newspaper lacks any note of the outcome of the trial.

|

AuthorDerek Saffie is an avid Windham historian who enjoys researching and sharing his collection with all those interested in the history of the New England town. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|