|

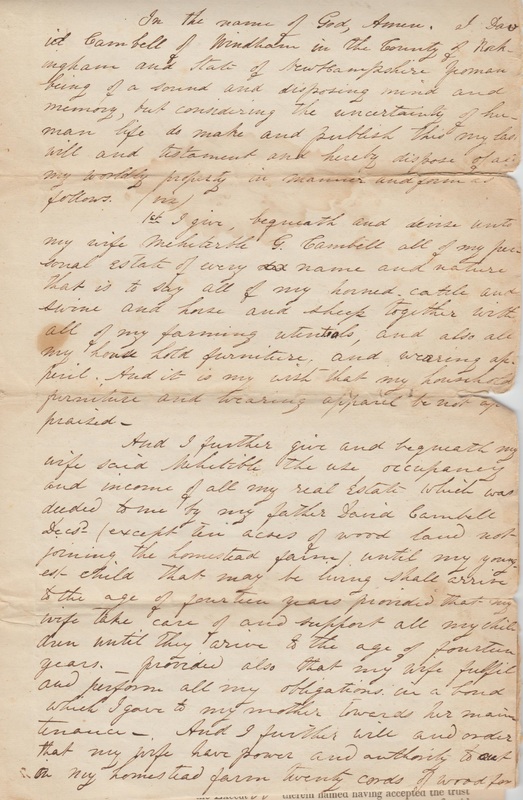

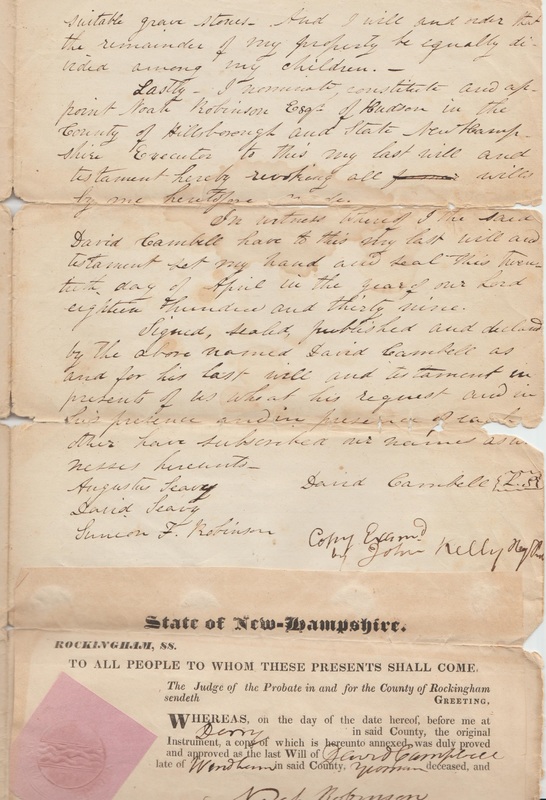

David Campbell, son of David and Elizabeth Dickey Campbell, was born on August 24, 1796. He lived upon the family homestead in West Windham and married Mary Marden. Tragically, Marden died at the age of 36 on February 3, 1837. Whether for practicality, or simply the need for companionship, David did not wait long before remarrying. Just several months after the passing of his first wife, David married the sister of his deceased wife, Mehitable, on September 14, 1837. Shortly after marrying Mehitable, David wrote a will bequeathing his entire estate to her. David died of consumption on June 5, 1839. Below is the last will and testament as written by David Campbell: First, David left all of his, "personal estate of every name and nature that is to say all of my horned cattle and swine and horse and sheep together will all of my farming utensils". Farming was not only a valuable source of income for many early Windham farmers, but also a necessity. The sheep would provide wool for clothing, and the pigs would have eventually found their way to the dinner table. Also, Mehitable was willed all of the, "household furniture wearing apperil [sic]", with the provision that such items were not to be appraised upon David's passing. Along with the material possessions, David left his wife, "the use occupancy and income of all [his] real estate which was deeded to [him] by [his] father David Campbell"; ten acres of woodland that did not adjoin the farm were excluded. However, there was the provision that Mehitable's occupancy of the homestead would last only until the couple's youngest child turned fourteen years old; there was also the contingency that Mehitable must take care of all the children until they are fourteen years of age. David did not leave his mother out of the will, ensuring that she will benefit from the sale of twenty cords of wood a year for every year that Mehitable lives on the property. He also added a provision that the executor of his estate provide Mehitable with a $50 stipend per year until the youngest child reaches the age of fourteen. When the youngest child did reach the age of fourteen, the rest of the real estate holdings were to be liquidated and $100 be donated to a missionary society.

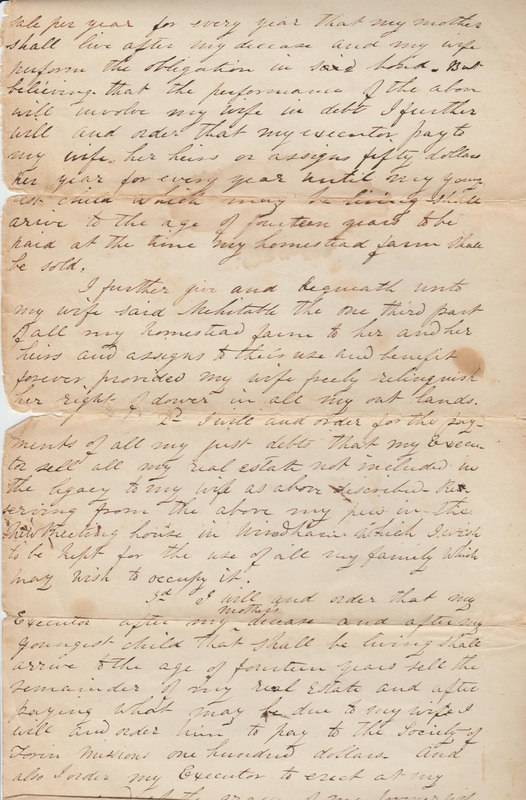

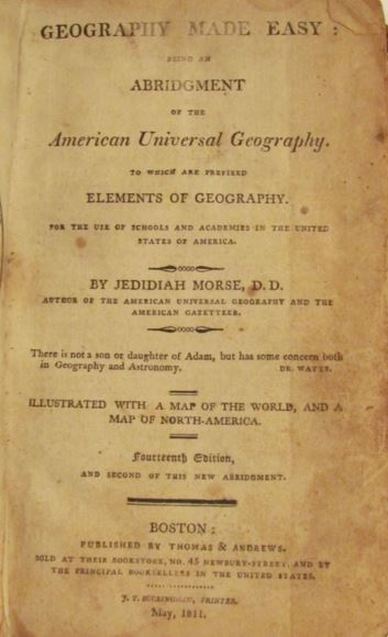

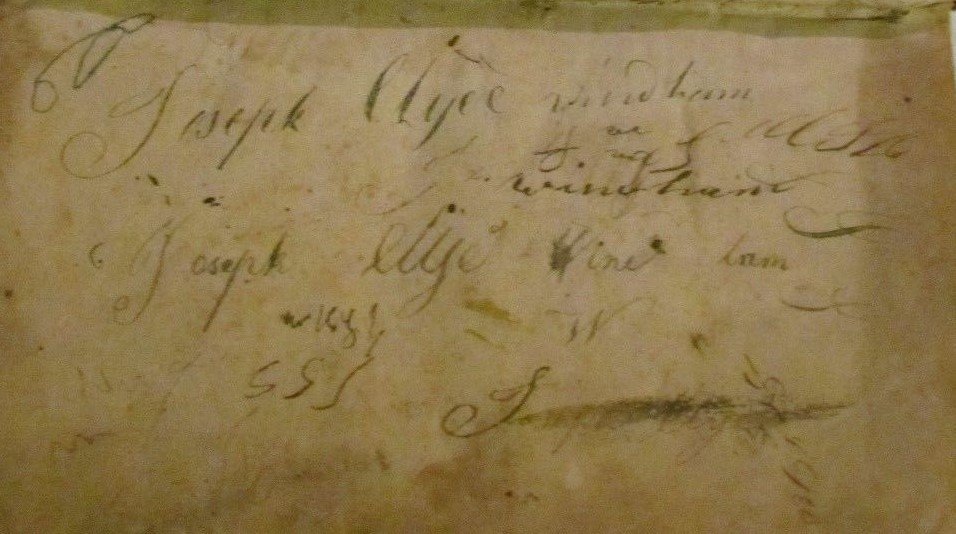

Laws in colonial New Hampshire mandated that towns meeting specific population requirements employ a schoolmaster for the education of the youth. In 1719, the same year the first settlers arrived in Nutfield, a law was enacted requiring that any town of over fifty households provide a schoolmaster to teach reading and writing. If a town had over one hundred families, then it was the responsibility of the town to have a proper grammar school. However, the law was vague regarding school houses, the laying out of school districts, and the formation of committees to run the schools. The law also mandated only male school teachers. Aside from elementary reading and writing, the grammar schools were required to teach both Latin and Greek. The towns that chose to disregard the law were fined £20. This rudimentary law remained in place until 1789 when it was replaced with a new law. The early Scotch settlers of Windham have been noted for their "love of intelligence", and schools were established shortly the first dwellings were constructed. Even though the first settlers were quite poor, they dedicated as much time to education as they could. It was not until 1727 that there was action taken to establish a grammar school in Nutfield. It was decided that for one year there would be no grammar school, on the contingency that two schools would be funded in the following year. Although there were as many as four schools in Londonderry in the 1720s, there is no record of a school being established in the town of Windham until 1766. John Aiken ran a singing school in town that year, and also taught reading in the eastern part of town. Also around that time, a former British soldier, Nicholas Sauce, was schoolmaster for four years in District No. 1. Sauce is recorded as being a "cruel teacher", for bringing the discipline of the British army into the classroom. With the possibility of a violent whipping impressed upon the minds of his students, the children would "tremble" each time they entered the classroom. Those who were often the subjects of the whipping began to place pieces of animal hide under their clothing to protect themselves. However, Sauce was an effective teacher, and greatly "advanced [his students] in their studies". The earliest schoolhouses in Windham were not built to be comfortable or lavish. Class would usually only be held in the schoolhouse during the summer, when the warm weather made sitting through lectures somewhat bearable. In place of a dedicated schoolhouse, class was held in shops or barns in some areas of town. During the winter months students would attend school in the private home of a generous neighbor. It would not have been unusual for the location of the "school" to move to a different house each week. Some families educated their children through "family schools". An educated parent or an older child would serve as a teacher for the younger children. The family of Captain Nathaniel Hemphill educated the younger generations through such a system. With a total of eighteen children the "school" educated as many students as some of the early schoolhouses. In a rural community where learned schoolmasters were often lacking, schoolbooks played a significant role in education. In the early days the only book used in education would have been the Bible. However, it would not have been long before the first academic books appeared in the schoolhouses of Windham. One of the earliest was "James Hodder's Arithmetic", which was published in London in 1719. Other early books included "Dillworth's Spelling Book" and "The Young Lady's Accidence". Geography books were not used until the turn of the 19th century, when Jedidiah Morse's books became commonplace. Similar books would have been used during the first few decades of the 19th century. Above is the back page from an 1811 copy of Morse's "Geography Made Easy", which belonged to Joseph Clyde Jr. Clyde was born on October 16, 1798 to parents Joseph and Elizabeth Wilson Clyde. He spent his life upon the family's homestead near the town center. Although copybooks for practicing penmanship were commonplace in the early schoolhouses, as a 13 year old student Clyde practiced a few of the most common words, his name and "Windham", that he would need to write, in the back of his school books. Above is an example, showing such practice as well as miscellaneous period writing. Clyde, who was the last representative of his family in Windham, tragically died on April 16, 1870 after being "thrown from his wagon, striking his head against the stone steps of Bartley's store".

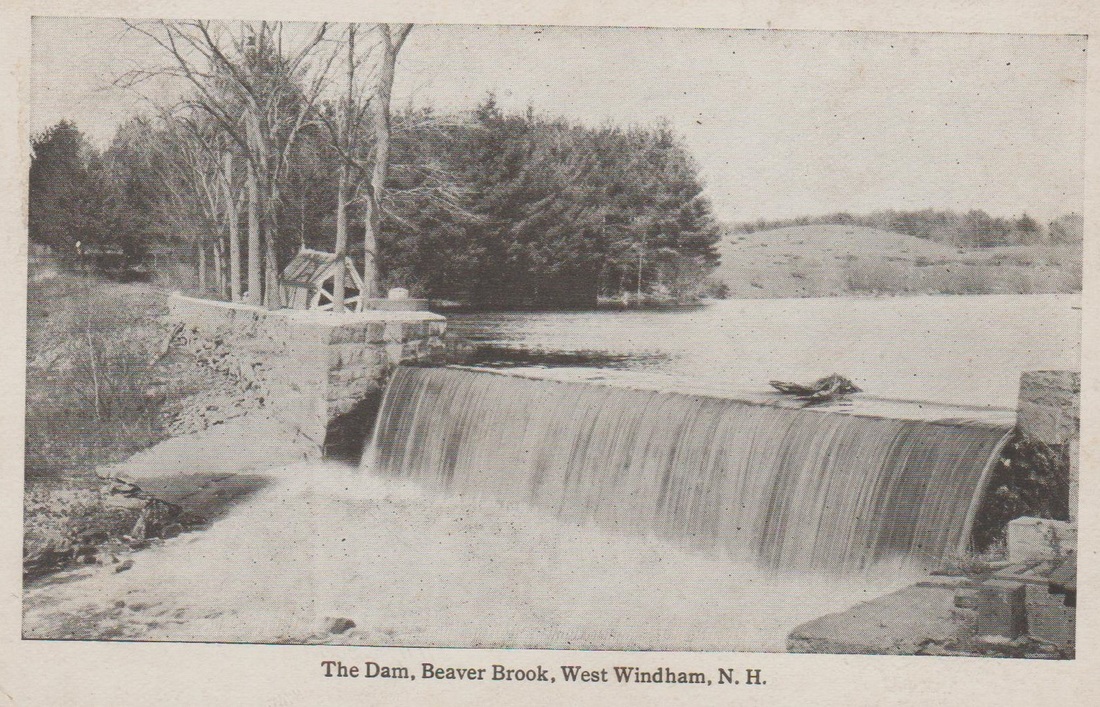

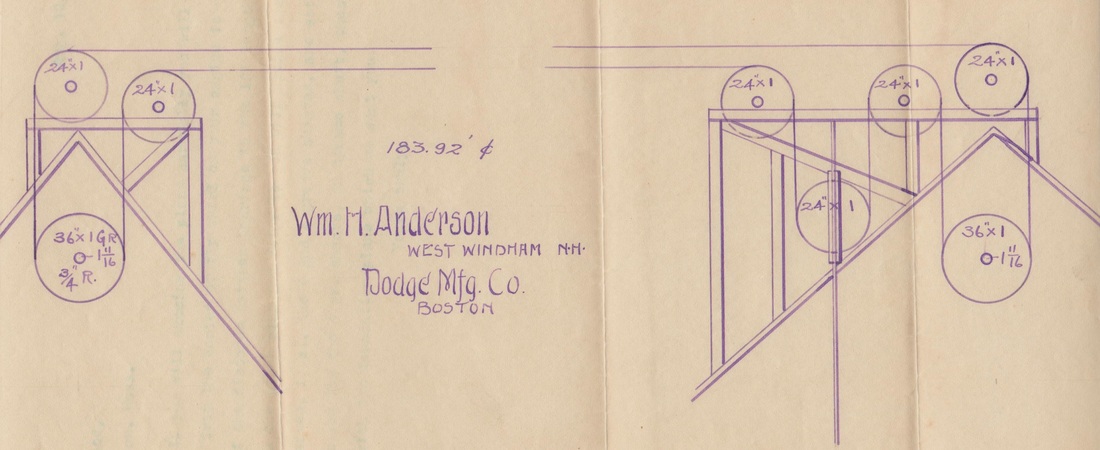

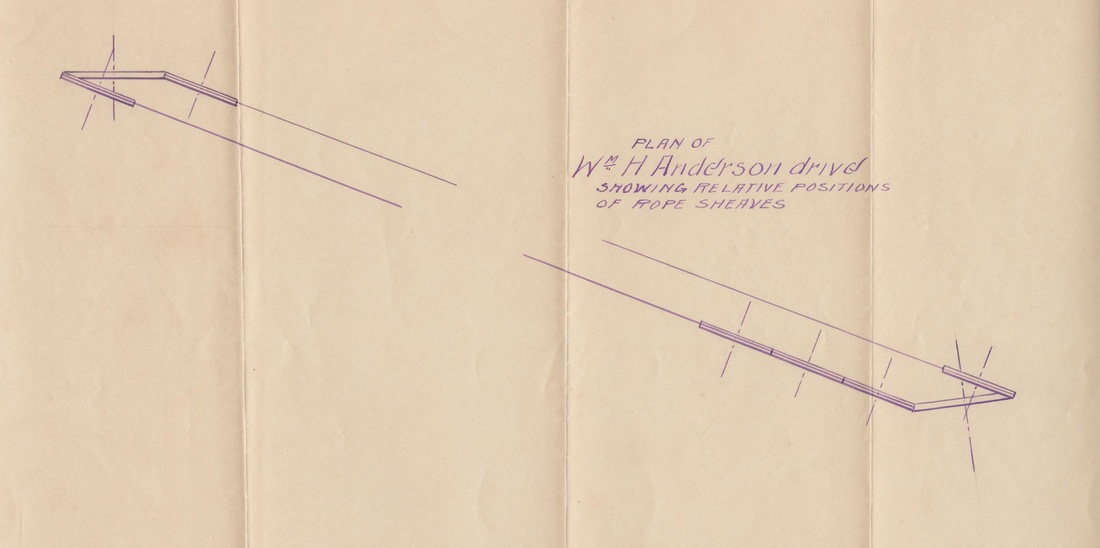

Beaver Brook proved to be a valuable source of power for the many mills that have operated on its shores since colonial times. However, many of the early mills were powered by large water wheels. The flow of the water would turn the wheel, which would then spin belts running machines, such as an industrial size saw. Many other local mills also took advantage of the power of water, including Neal's mill on Golden Brook. However, the dam fell into disrepair and by the late 1890s it completely let go; it was not rebuilt. In the first decades of the 20th century Walter Drucker's mill in West Windham was the last mill in town to still use water power. Drucker used the power to operate machinery to grind the grain that he sold from his small store in West Windham. Instead of using a simple waterwheel setup like the mills of centuries ago, Drucker utilized a more efficient, complex system of a wire belt and pulleys. His mill burned to the ground in 1896, but was rebuilt shortly after. It appeared as if luck was not on Drucker's side, as his mill burned again a few years later. In 1900, William H Anderson built a new mill, which is still standing today, on Beaver Brook. As he intended to harness the power of the brook, he engaged the Dodge Manufacturing Company of Boston to design a system to do so. Below are the blueprints drawn by the engineers at Dodge Manufacturing to propose their design to Anderson, as well as to aid in the construction of the system. As Anderson dedicated much of his time to his law practice, he did not intend to run the mill himself. Instead, he hired a Mr. Andrews of Arizona to operate the gristmill until 1910. Walton C Barker succeeded Andrews and managed the mill until 1921. The mill then ceased to operate for several years and was eventually sold.

There was a need for a blacksmith as soon as the first settlers arrived in Nutfield. A village blacksmith would be skilled in a variety of work, as it would have been necessary for him to service the numerous metal tools of centuries ago. It would not have been unusual for a blacksmith to fire up his forge in order to produce an ax, a hoe, a scythe, or even an iron plow. As horses were invaluable for farming and transportation, one of the blacksmith's most common services was the shodding of horses with hand fashioned horse shoes. However, oxen would not have been uncommon on the farms of Windham. According to Morrison, the process for shodding oxen was much more laborious than that for horses. One man would have been tasked with holding the head of the ox. The front legs and back legs of the animal would have been tied together to minimize the animal's mobility. The blacksmith would then attach the shoes to the ox with hand forged nails. However, this process was eventually replaced by the invention of a swing to suspend an ox above the ground for the procedure.

Above is an illustration of an apparatus similar to that of the first models introduced in around 1810. It was likely at least a few decades before the first swing for shoeing oxen arrived in the blacksmith shops of Windham. When wagons and carriages became commonplace, Windham's blacksmiths would have been tasked with repairing the vehicles. It was rather common for a blacksmith to repair the iron rim or hardware of a carriage's wood spoked wheel. With an increasing need for the services of a town blacksmith by the 1880s, Charles Perkins was able to hire two men in order to keep up with the demand for work. Perkins' shop burned to the ground in January of 1882 and there was no blacksmith in Windham for the next five years. Fortunately for many of the farmers requiring the services of a blacksmith, George Bugbee opened a blacksmith shop in 1887. Others began to see the lucrativeness of the trade, and the father and son team of Richard and Charles Esty opened their shop in Windham in 1888.

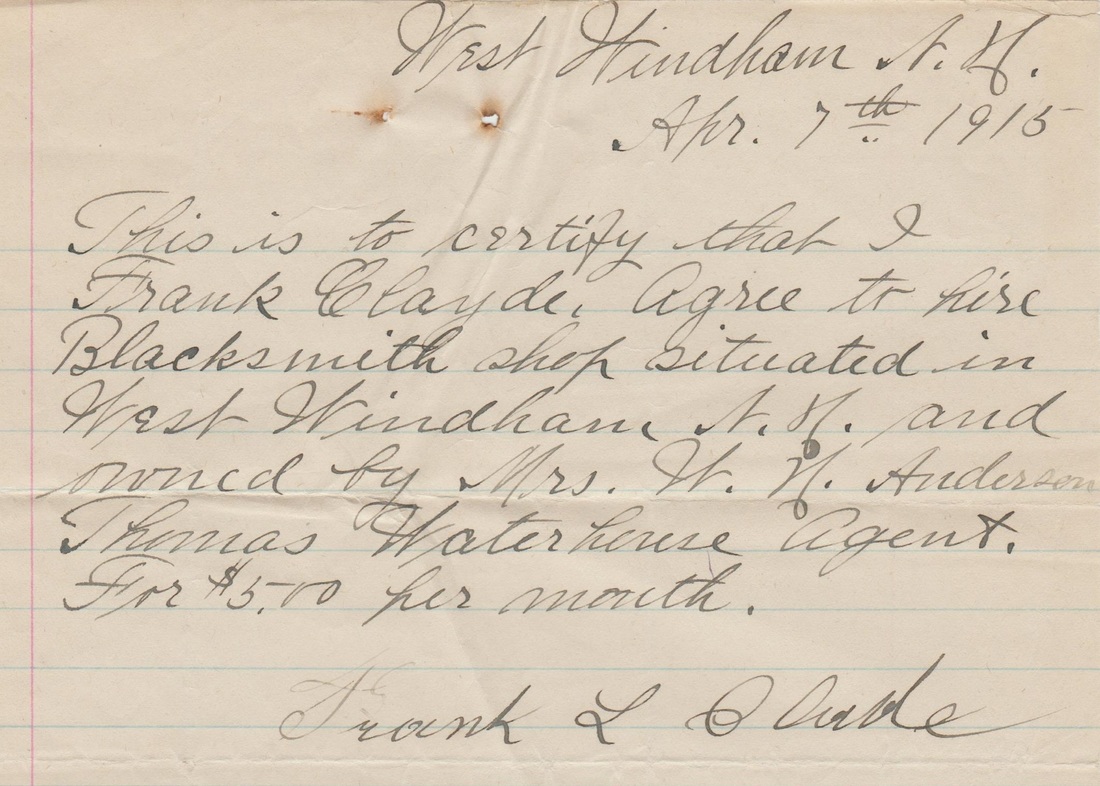

Although the Estys sold their business to A. Hamond and I.G. Goodwin in 1891, the shop was in operation until approximately 1908. In 1900 two more blacksmith shops were opened in town by E.A. Douglas and William Linsy. Shortly after the turn of the twentieth century the need for a blacksmith began to go the way of horse drawn carriages with the introduction of the automobile. Many of the tools required by the town's businesses and farms, such as axes and iron wrenches, began to become more available due to mass production; no longer was a blacksmith needed to forge a tool. Also, the automobile significantly reduced the usage of wagons and carriages. According to "Rural Oasis" E.A. Douglas was the last blacksmith in town, and remained in business until around 1910. However, as late as 1915 a new blacksmith came to Windham. Frank L Clayde leased a blacksmith shop owned by the wife of William H Anderson in West Windham, for the price of $5.00 per month. It is unknown how long Clayde remained in business at the West Windham shop.

|

AuthorDerek Saffie is an avid Windham historian who enjoys researching and sharing his collection with all those interested in the history of the New England town. Archives

November 2019

Categories

All

|